On Observability 2.0 and AI

For those that have read some of my previous blogposts, it might not be very surprising but I have a little thing for Mathematics. I’ve blogged a bit about my personal journey through learning academical mathematics as well as how others have explained it. Galileo Galilei is known to have stated “Mathematics is the language with which God has written the universe.”. Perhaps that has not really survived time well, but it’s clear where he’s coming from.

For most of our facts, we do not really have to rely on mathematics. Observability, whether grounded in measurability or not, has historically guided our sciences! I have seen it and therefore I believe! Even though we have gotten much better at this, it’s often still only available for a small number of people. As it can take years of training to be able to work on the much more abstract problems like String Theory and Topology, Nanobiology, Cosmology, or Climate- and Weather-modelling.

Next to that, explaining scientific progress or even (PhD-)student theses to the general public can be a work of art by its own.

This also holds true for systems-thinking and IT. Understanding a organization of buzzing engineers building a collective together with incomplete communication is often more of a science than a practice.

At least we can look at some metrics. We can perform some interviews to gain some logs or follow a process to obtain a set of spans and traces! That should definitely help us find the winning and slacking domains of our organization, right?

From Monitoring to Observability 2.0

Gartner once cited that 36% of its clients spend over $1M per year on observability, with 4% spending over $10M. 50% of that on logs alone. Charity Majors, CEO of Honeycomb and known for popularizing Observability 2.0 as industry standard, estimates from that particular Gartner Webinar that companies spend about 15-25% on observability (see [here]((https://www.honeycomb.io/blog/how-much-should-i-spend-on-observability-pt1) and here).

Looking purely at cloud observability, I’ve seen in the past that to be already good for 10%. Together with application observability through tooling such as Grafana Cloud, Splunk, etc, the estimations seem reasonable.

It should not really come as a surprise that Charity Majors advocates for appropriate observability data gathering in those 2 mentioned blog posts. On the hand that applies toew

Observability Pillars

Before Charity Majors coined the term observability, as well as Observability 2.0 for that matter, information was generated technically categorized by type and thereby also the storage solution.

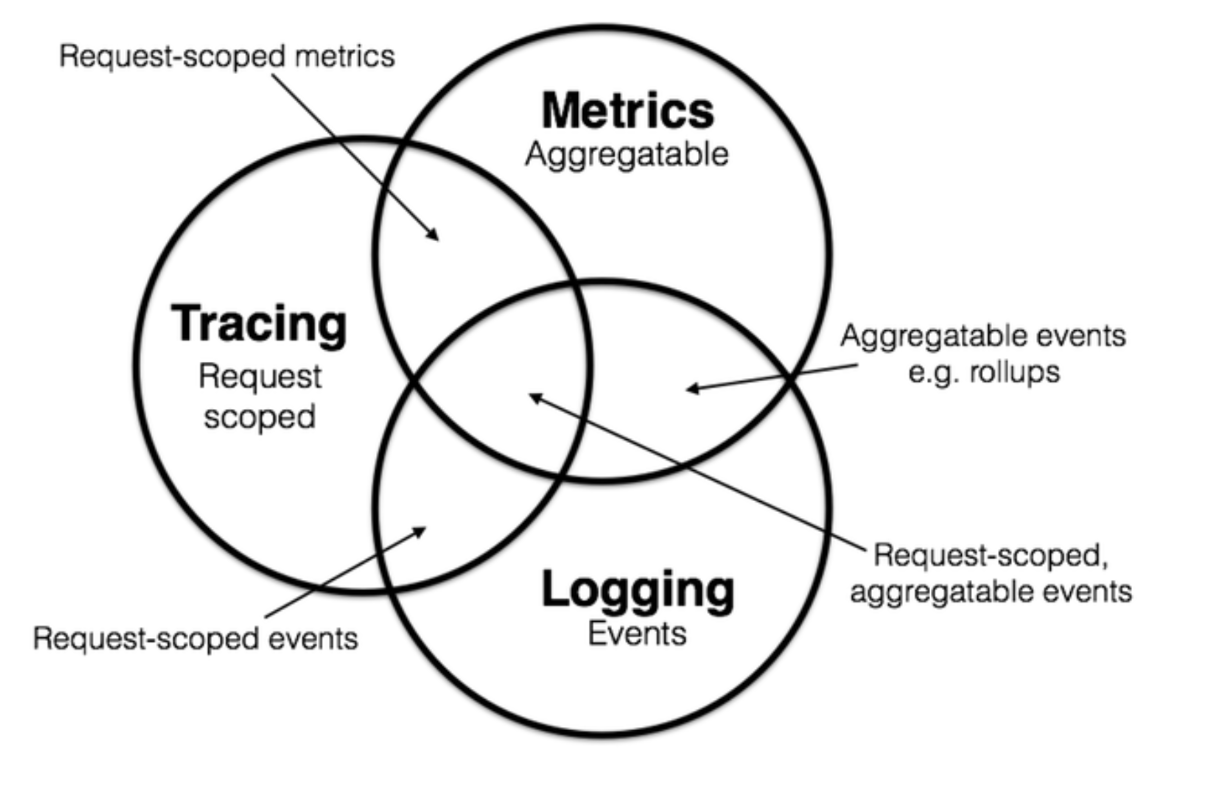

The source of these ideas come from Peter Bourgons in his blogpost.

- metrics is that they are aggregatable: they are the atoms that compose into a single logical gauge, counter, or histogram over a span of tim

- logging is that it deals with discrete events

- tracing, then, is that it deals with information that is request-scoped

Observability 2.0

Observability 2.0 moves beyond the traditional “three pillars” approach by emphasizing that telemetry data (logs, metrics, and traces) should not be siloed. Instead, these data types should be correlated and analyzed together to provide a holistic view of system behavior. While OpenTelemetry is often associated with Observability 2.0, it is primarily an open-source standard for generating, collecting, and exporting telemetry data, not the concept itself.

For example, logs alone can tell you what happened, but without traces, you cannot easily connect those events to specific requests or understand their impact on overall system performance. Similarly, metrics can show system load trends, but without context from traces and logs, diagnosing the root cause becomes difficult. Observability 2.0 advocates for breaking down these silos so engineers can ask arbitrary questions about their systems without predefining dashboards or metrics.

Nonetheless, storing and querying these three pillars in a more holistic matter only scratches the surface. As advocated by Honeycomb, the cost model of Observability 2.0 is very different.

For 1.0, your cost model depends on:

- How many tools you are using (this is often seen as a multiplier in this context)

- Cardinality (how detailed your data is)

- Dimensionality (how rich the context is)

2 out of 3, cardinality & dimensionality, are however the same drivers that make observability valuable in general! Meaning that by leaning on these 2 levers to rein in costs cannot help but result in worse observability!

For 2.0, because of a unified storage model and focus on the routing of information, your bill generally increases in line with:

- Traffic Volume

- Instrumentation Density

Instrumentation density is partly a function of architecture (a system with hundreds of microservices is going to generate a lot more spans than a monolith will) and partly a function of engineering intent.

Areas that you need to understand on a more granular level will generate more instrumentation. This might be because they are revenue-generating, or under active development, or because they have been a source of fragility or problems in your stack.

Your primary levers for controlling these cost drivers are consequently:

- Sampling (tail-based)

- With Observability 1.0 -> You throw away your most important data

- With Observability 2.0 -> You throw away your least important data

- Aligning instrumentation density with business value

- Some amount of filtering/aggregation, which I will sum up as “instrumenting with intent”

That’s pretty great, because that almost surely means that I get more Observability value for my investment! And that’s what Observability 2.0 is about.

Bringing AI & Agents into the Picture

Coming back to the introduction for this blogpost, since AI and Agents intrinsically are not deterministic, observability is becoming more important. Whether the goal is to debug what actually happened, or just to maintain an audit trail, without proper investments we simply will make another step back in the measurability of our processes.

Maybe they were not measurable beforehand at all, but with AI speeding up the process they might even become problematic. Either the process has to change, or other parts of that process would need to be become more efficient in order for the process as a whole to improve.